![Ruined Time Logo]](headers/ruinedtime.gif) |

|

| Homage to the Beat | |

| In the disturbing uncertainty of the new millennium it’s curious how the Beat Generation continues to haunt the American mind, especially since in the 1950s Beats seemed to be little more than a counter-culture revolution, a scattered collection of dissidents, poets, artists, writers, dropouts and social explorers who, after World War Two, found themselves disillusioned with the bloat of materialism. Essentially creative anarchists who experienced the mysticism of drugs, to the Beat “Beat” was a condition, a radical removal that denounced the mindless conformity of consumerism. | |

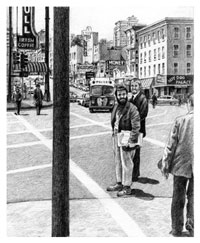

| In the late 1940s a Beat Generation was more-or-less centered in New York and San Francisco, where it was rooted in Greenwich Village, North Beach, and fringes of university neighborhoods across the country. Among so much else, the Beat learned from the Outsider how to create changes in lonely country places as well as foul cold-water flats in cities, which were heated in the winter by filling sinks with hot water - if a sink didn’t leak. In long or short runs the Beat learned it was better to follow yellow brick alleys in New York or San Francisco, because of the otherness in those two places. Walking to the San Remo, the Cedar Bar or the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village, it was possible to feel the rumble of the Atlantic, while - in North Beach - between The Place, City Lights or the Jazz Cellar, there was a whiff of Asian air coming off the Pacific. Since change was just a matter of getting up and going somewhere, it was decisive as long as someone somewhere knew where you were. |  Donald Graham and William Weisjahn, Broadway & Columbus, North Beach, 1958 |

In 1947 William Burroughs wrote to Allen Ginsberg from New Orleans and asked about the term “Beat,” which he’d heard from Herbert Huncke - who’d heard it from Jack Kerouac. Later, when John Clellon Holmes used the term “Beat Generation” in his novel, Go, Gilbert Millstein, an editor at the New York Times Magazine, asked him to write an article about it. "This Is the Beat Generation" was published on November 16, 1952.

|

|

Throughout the 50s the Beat was more of a literary eruption than a revolution. In 1953 Junkie by Burroughs led to Thom Gunn’s Fighting Terms in 54, to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Pictures From a Gone World in 55, to Ginsberg’s Howl in 56, to Kerouac’s On The Road in 57, and right through Gary Snyder’s Riprap in 59. Turned in or out by anyone or all of those works, Beats began to leave New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco for Paris, Tangier, Mexico City, Kyoto, and Bombay where they were free to see and feel more of who and what they were, and what they would never be - until they returned with older ideals and ideas of existence enhanced by foreign impressions, as well as ancient patterns of practice in which they saw that to be Beat was to not only to be galled with the commonplace, the corny and horny, but weary of failing to live an honest life in a technological-lized world. To be Beat was to create new rhythms in the mind - to get beyond the ordinary rush of raw life where it was possible to more than just live. Realizing this, opened up whole new worlds of seeing. Dissent, however, was always being revised. |

Bob Kaufman, North Beach, 1976 |

But there was always dissent. The jazz saxophonist Brew Moore once dismissed the insinuation that the Beats invented or epitomized the idea of Beat. Sitting in a rocking chair in a long flat out in San Francisco’s Mission District, Brew claimed that “almost every jazzman was born beat." Beat by the fact that people were afraid of the effect of jazz, especially in early Monday mornings when repetitious squares “slid back into their salty pegs." Years later there was more than dissent. After the Beat had become a legend, there were those who remembered sinks that leaked and reminded others who’d become icons of how lonely and rank it once was. Often on stage with Allen Ginsberg, who deserved superstar status, Gregory Corso would sometimes lovingly but pointedly temper Ginsberg’s exaggeration of his own thin, lonely roots by remembering those souls who in the early years had made an incredible difference - and had been forgotten. "Ginsie! Ginsie! Four people do not a generation make!!" (Gregory Corso to Allen Ginsberg in Richard Lerner’s film Kerouac, 1985.) |

|